College Admissions Tips and Guidance

Why Grit is Underrated

Explore Our Articles

Recent Posts

Popular Categories

Get In Touch

On Social

By Phone or Text

(617) 734-3700

By Mail or Email

1678 Beacon Street

Brookline, MA 02445

By Form

Educational Advocates

Our objective is to guide the family in finding options where the student will not only get admitted, but thrive and find success once on campus.

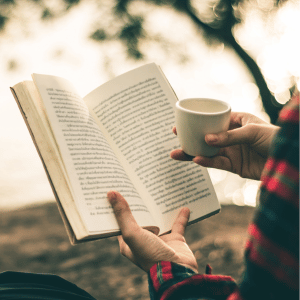

Why Grit is Underrated

I recently read Grit: The Power and Passion of Perseverance by Angela Duckworth. With a title like that, prior to even cracking the spine I was already inspired to think differently about my own determination and the determination of others–especially current students. After finishing the book, my educational experience—years full of learning about how I learned, slowly mastering skills that my peers caught onto fast, and ultimately feeling like I was missing the “how-to manual”—no longer felt like the burden it seemed to at the time. Instead, I saw the times when I had to study extra hard, ask more questions, and learn by failing first, as laying the groundwork for not only my success as a student and teacher, but also my perseverance as a human facing challenges and hardships. That was my journey, but what about the students currently in school? I know from being in the field myself that each student, three school years into this pandemic, is doing their best to navigate the changing and increasingly turbulent environment that has impacted their learning in ways only an extra dose of grit could possibly mitigate. These times are unexpected; however, Angela Duckworth’s Grit argues that a student’s success has more to do with who they are than what they have or what they have to face.

I recently read Grit: The Power and Passion of Perseverance by Angela Duckworth. With a title like that, prior to even cracking the spine I was already inspired to think differently about my own determination and the determination of others–especially current students. After finishing the book, my educational experience—years full of learning about how I learned, slowly mastering skills that my peers caught onto fast, and ultimately feeling like I was missing the “how-to manual”—no longer felt like the burden it seemed to at the time. Instead, I saw the times when I had to study extra hard, ask more questions, and learn by failing first, as laying the groundwork for not only my success as a student and teacher, but also my perseverance as a human facing challenges and hardships. That was my journey, but what about the students currently in school? I know from being in the field myself that each student, three school years into this pandemic, is doing their best to navigate the changing and increasingly turbulent environment that has impacted their learning in ways only an extra dose of grit could possibly mitigate. These times are unexpected; however, Angela Duckworth’s Grit argues that a student’s success has more to do with who they are than what they have or what they have to face.

When I was a student, I was bullied, but determined. I may not have fit in in the traditional ways, but I found a spot in the English department in high school and devoted myself to the teachers who believed in me. I also had a lot of passion, and though I was diagnosed with several language-based learning disabilities starting in kindergarten, I defied those diagnoses and became completely competent in reading and literature—scoring higher in those areas on every standardized test than the majority of my peers. Why do I think that is? Because I picked up a Dr. Seuss book and sat next to my dad for consecutive nights as I sounded out each word. Because my parents knew the importance of reading and so they supplied me with both a library card and the time to read before bed. Because I was lucky enough to have the support of learning specialists who supplied me with ways to problem-solve when I was at a young enough age that nothing seemed like too much. Because when I read I found a place in myself that had never been awoken before—it was an untouchable place saved solely for books—and I was going to do anything and everything I could to keep coming back. But, mostly, because I was and am stubborn when it comes to my determination and will to do something, even if it takes me longer than others. I had to study for hours at night. I needed to meet with the teachers for extra guidance. I often couldn’t pick up concepts right away. My visual learning style makes it so I have to see something first. Now, at 28, whenever I start a new job I actually ask my boss to be as hands-on as possible through training—no manual will teach me faster than their own demonstration. I’ve learned what works best for me, not because I fit into a box or checked off a list or kept my head down in classes, but because eventually I got tired of not knowing, and the quickest way for me to understand was to have the courage and passion to act and act for as long as it took.

In her book, Angela Duckworth defines grit as: “…working on something you care about so much that you’re willing to stay loyal to it…it’s doing what you love, but not just falling in love―staying in love.” For many students it isn’t a question of commitment, but of figuring out learning styles as a way to better stay engaged. Teachers can help with this process by staying informed about how our students learn best. Teaching an 8th grade class in Texas, I was met with the constant challenge of juggling classroom management, the day’s lessons, and a lot of unique, frustrated and distracted kids. The best lessons I gave were when I could connect one-on-one with each student in the classroom. When a student recognized that my attention was solely on them they would launch into questions and stories with complete wonder in their eyes and a determination—or grit—that came from being seen. I spent the majority of any given class bent over desks listening intently.

In college, students can choose their own classes, determine whether they want to learn virtually or in-class, at what times their brains seem to hold the most information. But students at a younger level need to figure out what works best for them through trial and error, something that isn’t always available. That’s where a student can help themselves—asking to meet with a teacher, carving out time to watch a playback of a lesson (if they are in virtual school), testing out their learning styles and figuring out if one particular one stands out best. A student has to be an advocate for themselves—it is their determination that ultimately guarantees their success—a success that might be unique to them, but that nonetheless is valid.

The pandemic has challenged our students in a myriad of ways. Throughout it all they keep coming to class, keep being assigned homework, keep graduating, and, hopefully, keep pursuing higher education with the hopes of discovering their capabilities and diving fully into their hopes and dreams. That’s a lot to put on any set of shoulders, especially a developing set. Grit reminds us that it isn’t about where we come from, but how we see ourselves. As Duckworth says, “…as much as talent counts, effort counts twice.” So, while a student may not be scoring as highly as their peers right off the bat, there is still hope that their dedication will continue to push them forward. Dedication cannot be directly handed off like an equation in math or a definition in English. Dedication has to come from within; fought for daily by the student, encouraged by the teacher and surrounding support system.

When we talk about passion and perseverance we also have to talk about failure. It can be difficult to see the light at the end of the tunnel, the payoff for all the work, when you just can’t get that one statistics formula down or when everyone else seems to understand the book, but you continue to struggle to make sense of a few words. About failure, Duckworth says, “I learned a lesson I’d never forget. The lesson was that, when you have setbacks and failures, you can’t overreact to them.” Each time you or your child finds yourself struggling, it’s an important reminder to take a moment to reset—even if a reset needs to happen frequently. Nothing fuels shutting down faster than failure. I watched my students quickly fold in on themselves if they received a grade lower than they had hoped, fearing failure was equated with who they were as people. One of my students, I’ll call her Sarah, scored low on an exam, and was crushed to tears. But she was also a fantastic volleyball player, and I reminded her that I would see her on the court that night, and, when she fell or missed a set, she wouldn’t give up, she’d just get up, put her shoulders back, and prepare for the next. “Ms. S,” she called the next day, “thanks for coming to my game.” If Sarah could believe in herself on the court, it followed that she could apply the same belief in the classroom. With a little extra encouragement, I had no doubt that she’d score high both on the court and off.

To learn more about what we do and how we can help your family click here.